The late Victorians loved their fairy tales, and playwright James Barrie, who had recently impressed London audiences with his plays Quality Street and The Admirable Crichton, thought he could take a risk on a particularly expensive play featuring a fairy, based on a character from his 1902 novel, The Little White Bird. He quite agreed with producer Charles Frohman that, given the elaborate staging Barrie had in mind, it would be quite a risk. But he had a second play standing by just in case. And, well, the neighbor children he’d been spending quite a bit of time with—sons of friends Arthur and Sylvia Llewelyn Davies—seemed to quite like his stories about Peter Pan.

The play was an immediate success, making Barrie wealthy for the rest of his life. (If not, alas, for one of those neighbor children, Peter Llewelyn Davies, who smarted under the dual burden of getting called Peter Pan for the rest of his life while having no money to show for it.) Barrie went on to write an equally popular novelization, Peter and Wendy, and others created various musical versions of the play—mostly retaining the original dialogue, but adding songs and the opportunity to watch Captain Hook do the tango. Barrie, everyone seemed to agree, had not just created something popular: he had created an icon.

If a somewhat disturbing one.

The inspiration for Peter Pan, the boy who refused to grow up, came from a number of sources: folklore; Barrie’s thoughts about dreams and imagination; his troubled marriage with actress Mary Ansell, which would end in divorce five years later; and his beloved dog, who inspired the character of Nana the dog, and thus entered literary history.

Another inspiration, which later helped inspire a movie about said inspiration, was Barrie’s friendship with the five young sons of the Llewelyn Davies family. Their mother Sylvia was the daughter of literary icon George Du Maurier, which helped cement the friendship, though originally they met thanks to Barrie’s overly friendly Saint Bernard dog. Barrie told them stories, used their names for the characters in Peter Pan and claimed that the Lost Boys were loosely based on them. The stories in turn led to the play, which led to the novel.

The most important inspiration, however, was probably an early tragedy. When Barrie was six, his older brother David, by all accounts a talented, promising kid, died at the age of 14 in a skating accident. Barrie’s mother never emotionally recovered. Barrie himself may have been too young to remember his brother clearly, or fully understand his death—although a couple of gossipy biographers, noting some discrepancies in various accounts, have suggested that Barrie, despite saying otherwise, might have been present at his brother’s death (and may have had some accidental responsibility), increasing the trauma and guilt.

Whatever the truth, Barrie did later claim to remember that his mother clung to one thought: at least her son would never grow up. It was an odd sort of comfort, something that stuck with Barrie, and helped inspire the idea of Peter Pan, the boy who would never grow up.

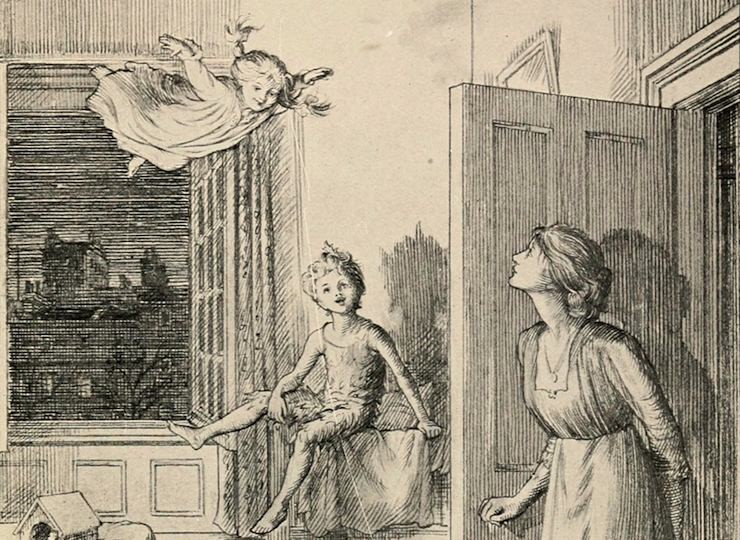

The story is more or less the same in the play, novel, and various musical versions. It opens with the Darling family—Mr. and Mrs. Darling, Wendy, John and Michael, and Nana the dog. In the book, the Darlings also have one maid who serves a minor plot function and who seems to be Barrie’s response to any audience members rather disturbed to see the Darlings happily trotting off to a dinner party despite knowing that a boy has been trying to enter the nursery for weeks and after removing their children’s major protector, the dog. As a defense, it fails, since it mostly serves to emphasize that the Darlings are just not very good parents, although Mrs. Darling does manage to capture Peter Pan’s shadow.

Total sidenote number one: the first staged version I saw of this was an otherwise terrible high school production that decided to represent Peter Pan’s shadow with a Darth Vader action figure. I now return you to the post.

Peter Pan enters the room, searching for his shadow, waking Wendy in the process. She pretty much instantly falls in love with him. It’s not reciprocated, but Peter does agree to take Wendy and the others to Neverland. In the play, this is merely a land of adventure and magic; in the book, it’s a bit more. He teaches all of them to fly, and they are off to Neverland.

Total sidenote number two: that high school production I mentioned dealt with the flying by having everyone walk off stage. This did not have the same emotional effect. Back to the post again.

Once in Neverland, Wendy gets to experience every woman’s wildest dream: finally finding a magical boy who can fly, only to realize that he just wants her to be his mother. It’s very touching. In the book, what this really means is made clear: a lot of laundry. Apart from that, she, Peter Pan and the Lost Boys have numerous adventures with pirates and, sigh, redskins (Barrie’s term, not mine; more on this in a bit) before returning home—leaving Peter Pan, who refuses to grow old, in Neverland.

The play is generally lighthearted, and charming, with its most emotional moment arguably more focused on the audience than the characters—the famous moment when Peter turns to the audience and asks if they believe in fairies. In most productions (that high school production aside), terribly worried kids clap as fast and as hard as they can until a little light brightens in Peter Pan’s hands. It might be corny, but with the right audience—small enthralled children—it absolutely works.

The novel is none of these things, except for possibly occasionally corny. It casts doubt on the reality of Neverland—something the play never really does—noting that everything in Neverland reflects the imaginary games that Wendy, John and Michael have been playing in the nursery. It paints Peter Pan not as a glorious flying figure of fun and adventure, but as a sometimes cruel manipulator. Oh, the Peter Pan of the play is certainly self-absorbed, and ignorant about certain ordinary things such as kisses, thimbles, and mothers, but he rarely seems to harm anyone who isn’t a pirate. The Peter Pan of the book often forgets to feed the Lost Boys, or feeds them only imaginary food, leaving them half starved; that Peter changes their sizes and forms, sometimes painfully. This last is done to allow them to enter their home through trees, granted, but it’s one of many examples of Peter causing pain. And he’s often outright cruel.

He also often cannot remember things—his own adventures, his own origin, his own mother. And so he makes others forget, sometimes to their benefit, sometimes not. The book strongly implies, for instance, that the pirates are quite real people dragged to Neverland by the will of Peter Pan. Most of them die. Don’t get too heartbroken over this—the book also clarifies, to a much greater extent than the play does, that prior to arriving in Neverland, these were genuinely evil pirates. But still, they die, seemingly only because Peter Pan wanted pirates to play with and kill.

The book also contains several hints that Peter, not content with taking boys lost by parents, accidentally or otherwise, has stepped up to recruiting children. We see this to an extent in the play, where Mrs. Darling claims that Peter Pan has been trying to get into the nursery for several days. But its expanded here. Those very doubts about the reality of Neverland raised by the book—that Neverland reflects Wendy, John and Michael’s games of “Let’s Pretend”—can also have a more sinister interpretation: that Peter Pan has planted those very ideas into their heads in order to seduce them into Neverland.

We can also question just how much going to Neverland benefits the kids. For the Lost Boys, I think Neverland has provided one benefit—although Peter doesn’t really let them grow up, or at least grow up very quickly, he also has no desire to take care of babies, so he does allow the Lost Boys to at least become boys, if nothing more, and he provides them with a home of sorts, even if he sometimes forgets them and even more often forgets to feed them. And even with the constant running from pirates, the Lost Boys never do get killed by them—that we know about.

But even this benefit has an edge. After all, they enjoy these adventures and eternal youth at a pretty steep price—isolation from the rest of the world, and from caregivers. And the book clarifies that the Lost Boys quickly forget their adventures in Neverland. Perhaps because Peter is furious that they were so eager to leave—and that very eagerness, and desire for parents, does say something—or perhaps because it’s easier and less painful to forget, but they do forget, and grow up to be very ordinary, seemingly unchanged by Neverland. Wendy alone doesn’t forget, but when Peter Pan doesn’t return every year to take her to Neverland, she’s devastated. So not forgetting has its own disadvantages. Though it does allow her to tell stories of Neverland to her daughter, summoning Peter Pan in the process. He rejects the grownup Wendy, and takes the daughter instead, because Wendy is too old.

Like, ouch.

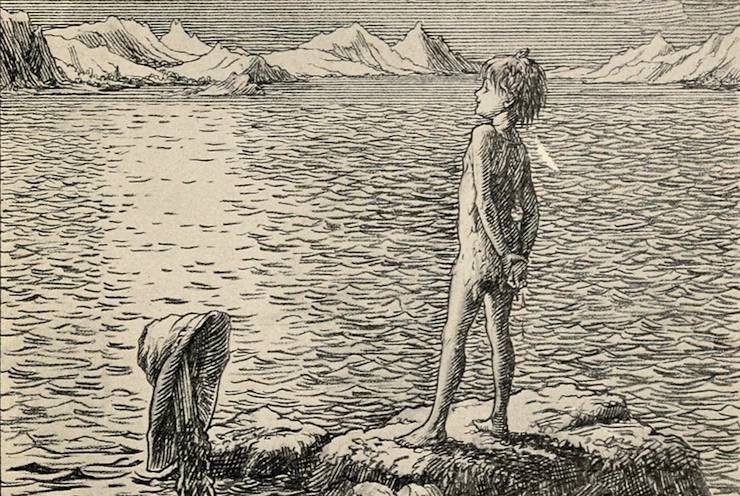

I don’t think, by the way, that any of this is meant to be approving: a strong theme of the narrative is that yes, everyone has to grow up, and trying not to grow up has harmful consequences for anyone who isn’t Peter Pan. The book has long scenes showing the Darling parents crying; the Lost Boys clearly want their mother; the pirates die. And it even harms Peter Pan. Sure, he has magic. He can fly. But he is ultimately alone, without any real, long lasting friends.

Even those you’d think would be long lasting, even immortal friends.

That’s right: I hate to crush the spirits of anyone who still believes in fairies, but in the book, Tinker Bell dies.

Speaking of which, the book also changes the famous “Do you believe in fairies?” scene from the play to a bit that allowed Barrie to grumble about the various small members of the audience who booed this scene or refused to clap: “A few little beasts hissed,” Barrie wrote, apparently unperturbed by the thought of insulting small children who had paid—or gotten their parents to pay—for tickets to his play. Then again, those were the same children who refused to clap for fairies. He might have had a point.

And now, sigh.

We need to discuss Tiger Lily and the redskins, don’t we?

It’s one part of the book that has not aged well at all, and which many readers will find offensive: not so much Tiger Lily herself, but rather, Barrie’s casual use of racist, derogatory language to describe Tiger Lily and her followers.

The only thing I can say in defense of any of this is that Tiger Lily and her followers are not meant to be accurate depictions of Native Americans, but rather a deliberate depiction of stereotypes about Native Americans. To his (very slight) credit, Barrie never claims that the Indians of Neverland have anything to do with real Native Americans – he even notes in the book that they are not members of the Delaware or Huron tribes, before saying that they are members of the Piccaninny tribe, like THANKS, BARRIE, I DIDN’T THINK THIS COULD GET WORSE BUT IT JUST DID (with a grateful sidenote to Microsoft Word for not recognizing that particular word or at least that particular spelling of it, minus a few points for not having an issue with “redskins.”) Like the pirates, they are meant to be understood as coming from children’s games, not reality.

Also the text continually assures us that Tiger Lily is beautiful and brave, so there’s that.

This is, to put it mildly, a rather weak defense, especially since Barrie’s depiction here is considerably worse than those from other similar British texts featuring children playing games based on stereotypes about Native Americans, not to mention the rather large gulf between perpetuating stereotypes about pirates, and perpetuating stereotypes about ethnic groups. In an added problem, the pirates—well, at least Hook—get moments of self-reflection and wondering who they are. Tiger Lily never does.

Even the later friendship between the Lost Boys and Tiger Lily’s tribe doesn’t really help much, since that leads directly into some of the most cringeworthy scenes in the entire book: scenes where the tribe kneels in front of Peter Pan, calling him “the Great White Father,” (direct quote), and following this up with:

“Me Tiger Lily,” that lovely creature would reply, “Peter Pan save me, me his velly nice friend. Me no let pirates hurt him.”

She was far too pretty to cringe in this way, but Peter thought it his due, and he would answer condescendingly, “It is good. Peter Pan has spoken.”

Not surprisingly, some stage productions have dropped Tiger Lily completely or altered her (not many) lines to eliminate stuff like this. The later Fox television show Peter Pan and the Pirates kept the characters, but made numerous changes and removed the offensive terms, along with adding other minority characters. (Mostly token minority characters, granted, but still, it was an attempt.) The book, however, remains, as a historical example of the unthinking racism that can be found in books of that period.

While we’re discussing this, another unpleasant subject: misogyny. Peter Pan does get full credit for featuring two girls, Wendy and Tinker Bell, as prominent characters, plus a few side characters (Tiger Lily, Mrs. Darling, Nana, Jane and Margaret.) And I suppose I should give Barrie a bit of credit for placing both Tiger Lily and Wendy in leadership roles.

And then there’s the rest of the book.

The mermaids, all women, are all unfriendly and dangerous. The pirates claim that having a woman onboard is unlucky—granted, Barrie was referring here to a common British saying, but given that having a girl on board does, in fact, lead to extremely bad luck for the pirates (the ship escapes), I get the sense that we are half expected to believe in this statement. Wendy spends the first couple of scenes/chapters desperately trying to get Peter to kiss her. She then finds herself forced into a mother role. The text claims that this is always something she’s wanted—backed up when Wendy later happily marries and has a daughter. But what it means is that everyone else gets to have adventures; Wendy gets to scold all of the Lost Boys into going to bed on time. Peter Pan gets to rescue himself from the dangerous rocks; Wendy has to be rescued. And she hates the pirate ship not because it is crewed by pirates, but because it’s filthy.

And Wendy, in the end, is the one who ruins Neverland for everyone, by reminding the Lost Boys about mothers. It’s a not particularly subtle message that girls ruin all the fun.

At this point you might be asking, anything good in the book? Absolutely. For all its misogyny, Mrs. Darling comes off as considerably wiser and better than her husband, which helps. The writing ranges from lyrical to witty. And for all its cynicism, it still retains an element of pure fun and joy.

What I’m saying is, this is a mixed up book that I have mixed up feelings about. It has deep and beautiful things to say about imagination, and courage, and growing up, and not wanting to grow up, and death, and living, and parents, and escape. It has brilliantly ironic lines, and lovely images, and mermaids, and pirates, and fairies. It has racism, and sexism, and anger. And an embodiment of a thought many of us have had as children or adults: that we don’t really want to grow up, that we do want to escape into an endless land of adventures, without any responsibility whatsoever, and the price we might have to pay for that. Not an easy book, by any means, but proof that Peter Pan did not become an icon just by refusing to grow up.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.